There is more to know than just what you can count

Powerful testimony from the covid inquiry on the limits of what data can convey.

The covid inquiry is well into the third of ten weeks of hearings on its third module – this one focussing on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare systems. The media coverage around this module has been less frenetic than its predecessors, in part because of the lack – thus far – of “star” political witnesses who draw in the big crowds of journalists. Nevertheless the testimony in this module has been no less compelling for those following the minutiae of proceedings.

Yesterday it was the turn of Chris Whitty to testify, which brought more media attention to this module of the inquiry. Arguably though, it was Professor Kevin Fong – the former national clinical adviser in emergency preparedness at NHS England - who provided the most compelling testimony of the day.

Reporting from his experiences visiting different healthcare settings during the acute phase of the pandemic, Fong tried to convey to the inquiry the depth of the shortages experienced by some units in the face of the unprecedented numbers of patients. Quoting one consultant he summarised “We ran out of equipment, we ran out of drugs, we ran out of nurses, we ran out of good will.” He described healthcare professionals wearing cagoules and waterproof trousers because there simply wasn’t enough PPE to go around.

In response to a different question, Fong recalled the testimony of hospitals experiencing previously unheard of levels of death. One hospital he spoke with reported 10 deaths in a single shift including two of their own staff. “These people are used to seeing death” he said, “but not on this scale and not like that”. At times visibly emotional, he described testimony from nurses who were forced to leave recently deceased patients in body bags on the floor of the ward in order to make room on the bed for the constant influx of new patients “raining from the sky”.

In order to ease the pressure on smaller hospitals, Fong described a practice which saw some of the more stable patients - those who were well enough to survive the journey - shipped off to larger hospitals for treatment. Of course, this left the most unwell and critical patients at the smaller hospitals. Fong suggested that some of them experienced mortality rates in excess of 70% over the weeks following the patient transfers – “seven out of ten of every patients that they had died”. Breaking down in tears Fong described the impact this had on these isolated smaller units, suggesting that they blamed themselves for the high mortality rates, when in fact this was a common experience across multiple units during that covid surge.

Touching on the trauma experienced by healthcare workers, Fong described the hitherto almost unheard of experience of video calling loved ones so that they could “say their last goodbyes” to dying patients. But according to Fong’s testimony the euphemism “say their last goodbyes” doesn’t even come close to capturing the experience of relatives “imploring the patient not to die” or “howling down the phone”. Healthcare workers were left with no option but to intrude on this most private of moments and to be “entrained into that grief” over and over and over again.

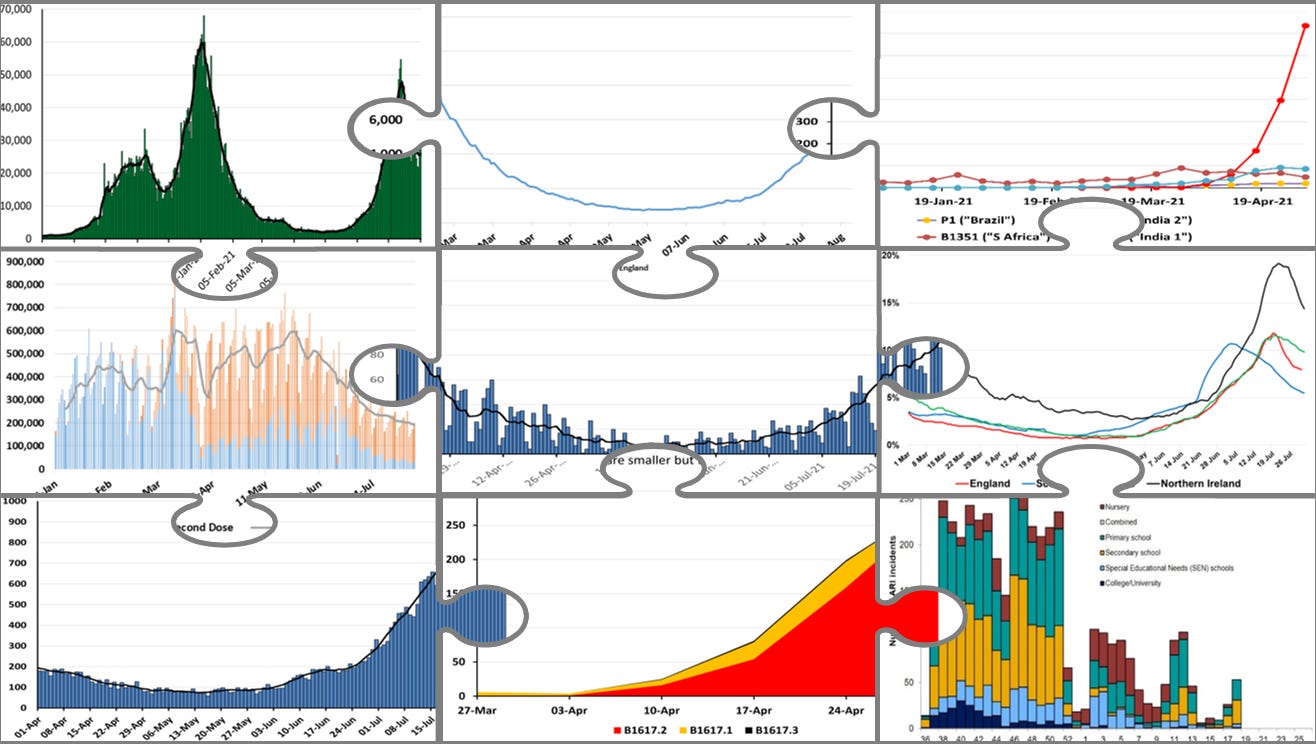

During the acute phase of the pandemic, I and my Independent SAGE colleagues Christina Pagel and Duncan Robertson (ably assisted by our data supremo Bob Hawkins) tried to paint a picture for the public of what was happening with covid cases, hospitalisations and deaths, by visualising the data we had available to us on the latest peaks and troughs. We dug into what was available, drilling as deep as we could and trying to provide nuance to the data visualised on charts and graphs with our explanations and interpretations. Although I think we captured one side of what was going on – we were able to give people a steer as to what they might expect in the near-future as the pandemic progressed – there was no way to convey the horror of the magnitude of the catastrophe that was unfolding. No way for us to paint a picture of what it was like dealing with the realities of death on an unprecedented scale. There was nothing we could do with the data to tell people what it was like to watch tens of people die a day, including your own friends and colleagues.

Fong touched on this very problem towards the end of his testimony. Again becoming visibly upset, he describes how hard it was for anyone to really get a sense of what was happening on the front line without being there themselves. “You don’t know unless you’re the people who’ve run out of body bags and are putting people in plastic sacks. You don’t know if you’re not the people who’ve held onto iPads while relatives are screaming down the phone. You don’t’ know if you haven’t sat in transfer vehicles next to a patient who’s dying of covid, wondering if your PPE is buttoned up well enough that you might do the same. It is impossible to know”. “Although this is not hard numerical data,” as we found out ourselves and as Fong so eloquently put it, “there is more to know than just what you can count”.

I watched the Covid Inquiry and was so distressed listening to Professor Kevin Fong. I was also angry remembering those ‘leaders’ clapping weekly for HCWs only to treat them with so much disrespect.

Those same ‘leaders’, both politicians and scientific advisers, lost my respect, trust and faith early on due to their lack of openness, honesty and integrity. For those reasons I was relieved to find the scientists of Independent Sage in May 2020 and was grateful for the briefings, discussion and the range of scientists answering questions from the public. I thank you and your colleagues as I continue to follow today to keep myself informed.