The One-Point Slam

An unusual tennis competition that pits amateurs against professionals in one-point matches is launching at the Australian Open. But could an unknown player really take down one of the world's best?

It would be a sporting upset like no other – an unknown amateur beating the world’s greatest tennis players to a million-dollar prize.

Yet this is exactly the opportunity being dangled at this year’s Australian Open tennis Grand Slam. Running during the qualifying week for the main draw (on the 14th of January) will be the One Point Slam, where each “match” hinges on just a single point played on court. And the competition is open to amateurs as well as professional players.

To take home the A$1 million (£490,000/$672,000) prize fund, all you’d have to do is win five or six points. So how can an unknown amateur defeat the world’s top tennis players to clinch the title? Let’s look at the maths.

There will be 48 competitors in total – 24 professional players alongside eight amateur winners of earlier state championship rounds played across Australia in 2025. There will also be eight players (amateurs or professionals) who will pass through qualifying rounds in the opening week and eight wildcards – celebrities and invited personalities. The pros count the men’s world number one and two, Alcaraz and Sinner, as well as Australian fan-favourite Nick Kyrgios. Swiatek and Coco Gauff, the women’s world number two and three, are also due to take part. So the competition is likely to be tough.

But it is the single-point format that makes the chance of an upset – of an objectively worse player beating an objectively better player – more likely. It gives an amateur their best chance of beating a pro.

A single point provides less opportunity for the better player to assert their dominance and more chance for a simple mistake or blind luck to come into play. The organisers are gambling that this is exactly what the people watching the tournament will want to see.

This isn’t always the case. Most sports fans want to see skill triumph over luck. Typically, we like our sports to reduce the chance that a weaker player wins by luck. We usually want to see the best players battling it out in the later stages of a tournament, putting on a show rather than getting knocked out early on.

And there is a simple mathematical rule that allows tournament directors to make this happen. As the number of points played increases, the chances of the better player winning don’t just stay the same - they also increase. The more points played, the more the better player can exploit their advantage.

Let’s think of a really simple scoring system, in which the first player to reach some predefined number of points, N, is the winner. Fencing, for example, uses a first-to-15 format based on the number of touches landed on an opponent.

It turns out that if players are relatively evenly matched, then there’s a nice mathematical formula that tells you how often you would expect the better player to win the match as the number of points increases.

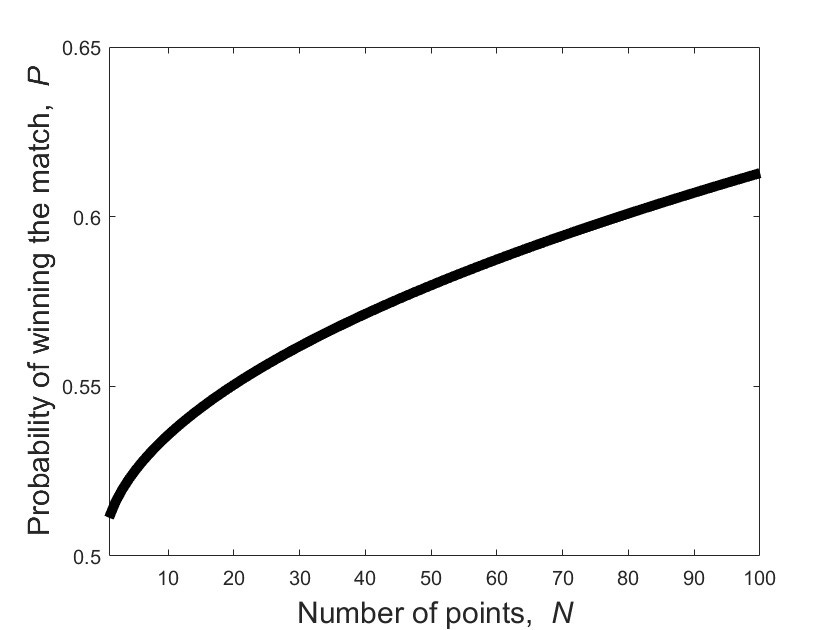

Let’s assume that the better player wins each point with probability p = 1/2 + a, where the advantage, a, is small because the players are close in skill. For example, if one player has probability p = 0.51 of winning each point, then the advantage, a, is just 0.01. Then, over a first-to-N match, we expect the better player to triumph with probability

The amount by which this number is bigger than a half is

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this tells us that the probability of victory increases with the advantage, a. But it also tells us that this win probability increases as the square root of the number of points needed for victory, N (see the figure above).

To make sure the winner gets a sufficient advantage, and to ensure that the match is long enough to be worth the spectator’s while, we need to make sure a sizeable number of points is required for victory. But we also don’t want players to build up unassailable runaway leads, so matches rarely comprise just one first-to-N-points competition. Instead, in sports like table tennis, squash and badminton, they’re broken down into games, and the first player to win a fixed number of games wins.

For a competition that is the first to a certain number of games (M) with the first to N points winning a game, we can again work out the probability of a player with the same slight advantage, a, going on to win the whole match. It turns out that this is

This time the all-important skill-to-luck ratio depends on the factor N × M (number of points per game multiplied by number of games). If we want to increase the reliability of the better player winning the match we can increase either the number of points played per game, or the number of games. Similarly, to add more unpredictability to the outcome we can reduce either of these factors. And, by reducing both of these factors to their lowest possible value of one, this is what organisers at the Australian Open are hoping their One Point Slam will achieve.

It’s not the first time a sport has tinkered with the scoring system to spice up the game for spectators. In table tennis, for example, the scoring system used to be first to reach two games. Each game was the first to reach 21 points, with the winning player needing to win by two clear points. Remember that the factor which determines the skill-to-luck ratio is the number of points needed to win a game multiplied by the number of games needed to win a match - giving 2 × 21 = 42 in the original scoring system.

The problem was that, in the race to 21 points, one player could quickly get quite far ahead in a game, meaning that the opponent was effectively out of contention, reducing interest in that game for spectators and players alike. So, in 2001, organisers decided to reduce the number of points needed to win a game to 11. To balance this out, they increased the number of games needed to win a match to four.

In a smart move by the International Table Tennis Federation, this actually didn’t dramatically change the overall skill-to-luck ratio inherent to the matches (because the all-important factor worked out to be 4 × 11 = 44 in this new format, similar to the factor of 42 in the original). But it made the games more exciting for fans.

Beyond sport, the same idea – that adding independent components tends to improve accuracy – shows up in areas as diverse as law and medicine. If each juror is slightly more likely than not to be right, larger juries make a correct majority more likely. In medicine, doctors can use multiple tests on the same patient to refine the accuracy of the outcomes. In each case, the same principle holds: changing how many trials we take or how many components we include dials the role of luck up or down.

Returning to tennis, the key to the skill-to-luck balance is the number of points to win a game – four – multiplied by the number of games to win a set – six – and the number of sets to win a match. Roughly speaking, the higher the resulting number is, the more likely the better player is to win out overall.

This is perhaps part of the reason why there is more variability in the winners of the women’s Grand Slams than the men’s (since 2000, there have been 37 different female Grand Slam winners and only 22 different male Grand Slam winners). In the Grand Slams, men play first to three sets while women play first to two, meaning there is a greater chance for less-favoured players to win.

The One Point Slam is a world away from a five-set Grand Slam tennis match and it’s a good job too. With such a big difference between an amateur and a pro, it’s unlikely that the amateur would ever be able to prevail over a whole match, a set or even a single game. Even playing just a single point against the world’s top tennis players is a hard ask. The pressure alone could cause an amateur to crack. But the maths shows that the one-point format provides the best possible chance of an upset.

Even if an amateur doesn’t get to claim victory over Carlos Alcaraz – they will still be able to say they took the men’s world number one to match point. And that’s quite a brag.

This post is adapted from my article on BBC Future.