Et in Arcadia ego

Maths, desire and time’s arrow meet at the Old Vic: as I discover as Arcadia's science consultant

I have some exciting news to share. I’ve been working as the maths/science consultant for the new production of Sir Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia, which begins its run at London’s Old Vic this week (starts Saturday 24th January). I’ve been running sessions with the cast, directors, producers and stage designers in order to help make the science and maths as authentic as possible.

The play weaves big scientific ideas through a story of curiosity, desire and the passing on of knowledge. You don’t need a background in physics to follow what’s at stake. Stoppard’s characters - scientists, scholars and poets across two time periods (early 1800s and the ‘present day’ (originally 1993)) in the same Derbyshire house - keep asking what can be known, what remains uncertain, and how the world’s messiness can be represented by the elegant equations of mathematics. The science is quite broad-ranging from Fermat’s Last Theorem and the Second Law of Thermodynamics to Chaos Theory and the mathematics of natural forms.

So I thought I’d share some of the insights I shared with the actors so you have a head-start on the maths in case you decide to take yourself down to London to see the play over the next few months.

The clockwork confidence of Newton

For centuries, Isaac Newton’s laws underwrote an almost clockwork-like vision of the universe: if you know the positions and speeds of objects – from planets to particles - and the forces acting on them, you could, in principle, calculate what they will do in the future. The textbook toy model used to exemplify the utility of Newton’s laws for prediction is a frictionless billiards table; measure how the cue ball is hit precisely and the positions and velocities of all the other balls’ paths - arbitrarily far into the future - should be available through calculation. In Arcadia’s Regency timeline, teenage maths prodigy, Thomasina Coverly, is educated inside that classical frame, while her tutor, Septimus Hodge, voices the ethical and philosophical consequences: “If everything from the furthest planet to the smallest atom of our brain acts according to Newton’s law of motion, what becomes of free will?” This plants the seed of the battle between determinism and free will early on in the play and we watch that idea flourish and grow as the drama unfolds.

Determinism and Newton’s laws are also used in the play as the jumping-off point to bring in another idea: irreversibility. Newton’s equations of motion tend to draw smooth, reversible curves. If you run a film of planets obeying Newton’s laws backwards, it still looks plausible - none of the laws have been violated by reversing the movie, only the direction of time has flipped. But in the real world most processes are not reversible and this is another theme that comes up over and over again in the play.

Total Chaos

In the twentieth century, scientists began to take an interest in systems that obey strict rules yet can diverge significantly in response to tiny differences in initial conditions: a characteristic of chaotic behaviour. Back in the 1960s, meteorologist Edward Lorenz found that a tiny rounding error halfway through his weather model pushed the forecast onto a completely different path from the version where the error didn’t occur.

Popularised as the “butterfly effect”, this insight - sensitive dependence on initial conditions - doesn’t counter determinism – these systems are still completely determined by their initial conditions and the equations that govern them; but it does show why predicting the future is, for many systems, so difficult as to be practically impossible. In Arcadia, Stoppard explicitly acknowledges a debt to modern chaos theory and the popular science that brought it into view; it’s part of the modern characters’ world just as Newton was part of Thomasina’s.

Chaos in the drama becomes more than mathematics. As the godfather of chaos, Lorenz (he of the broken weather model above), put it: “Chaos: when the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future”. That line of thought mirrors the modern timeline plot, where scholars try to recover a past event from partial traces and find their reconstructions veering wildly with each new scrap of evidence from the past.

The humble loop that drives chaos: iteration

One of the classic ways into chaos is through iteration: take a rule, compute an output, feed that output back as the next input and repeat. In particular, chaos has been found in the models of populations that vary from year to year. In the 1993 timeline, Valentine Coverly explains that he is using exactly this sort of model to represent grouse populations. He stresses that with the real data he is using, “it’s not nature in a box,” so you never capture every gust of wind or every fluctuation in the fox population that eats the grouse, and the record – the data he is working from – is always messy: “It’s all very, very noisy out there. Very hard to spot the tune”. Yet he is adamant that the long‑term behaviour can still be represented by a mathematical equation: “…it isn’t necessary to know the details. When they are all put together, it turns out the population is obeying a mathematical rule.”

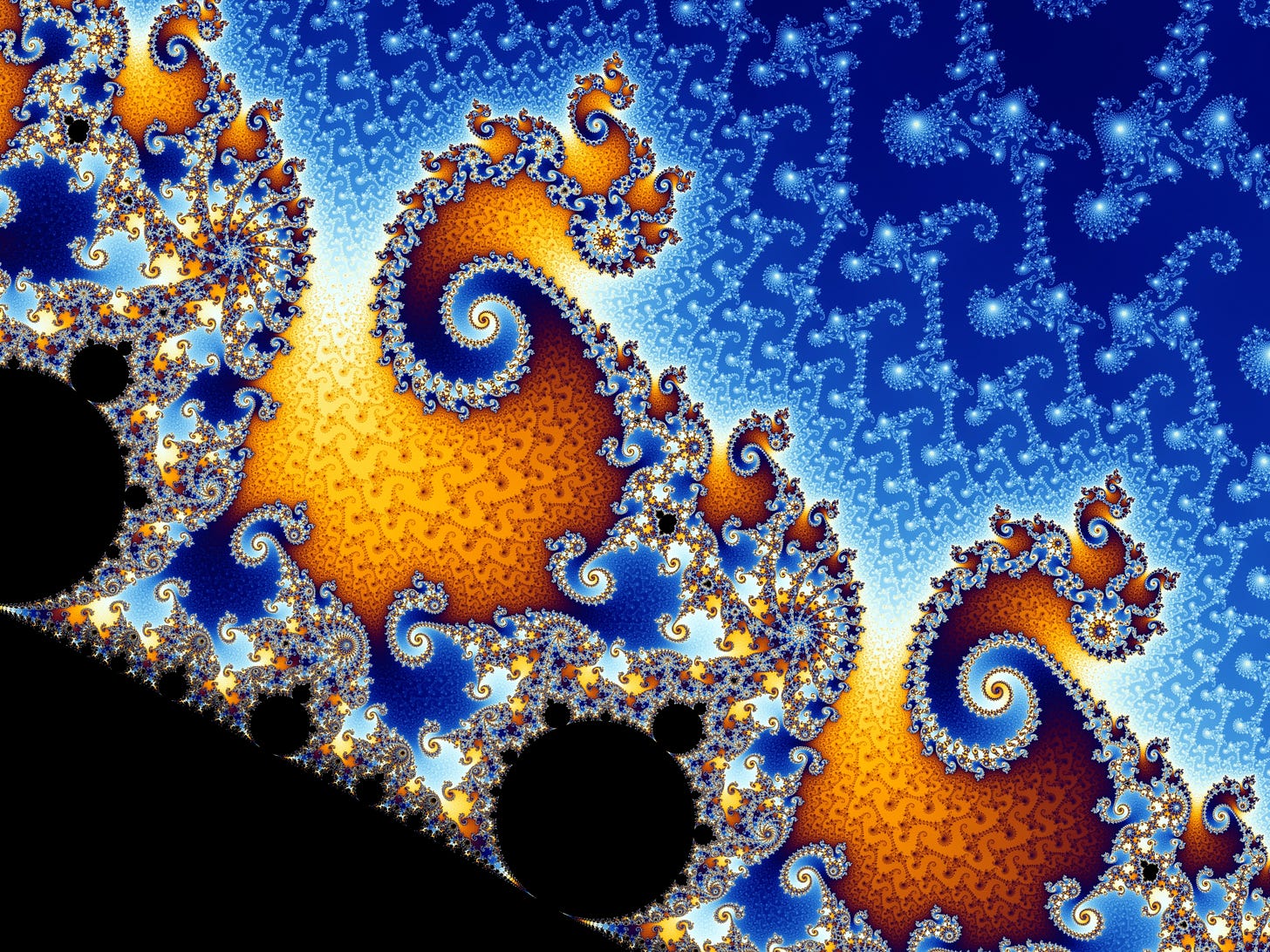

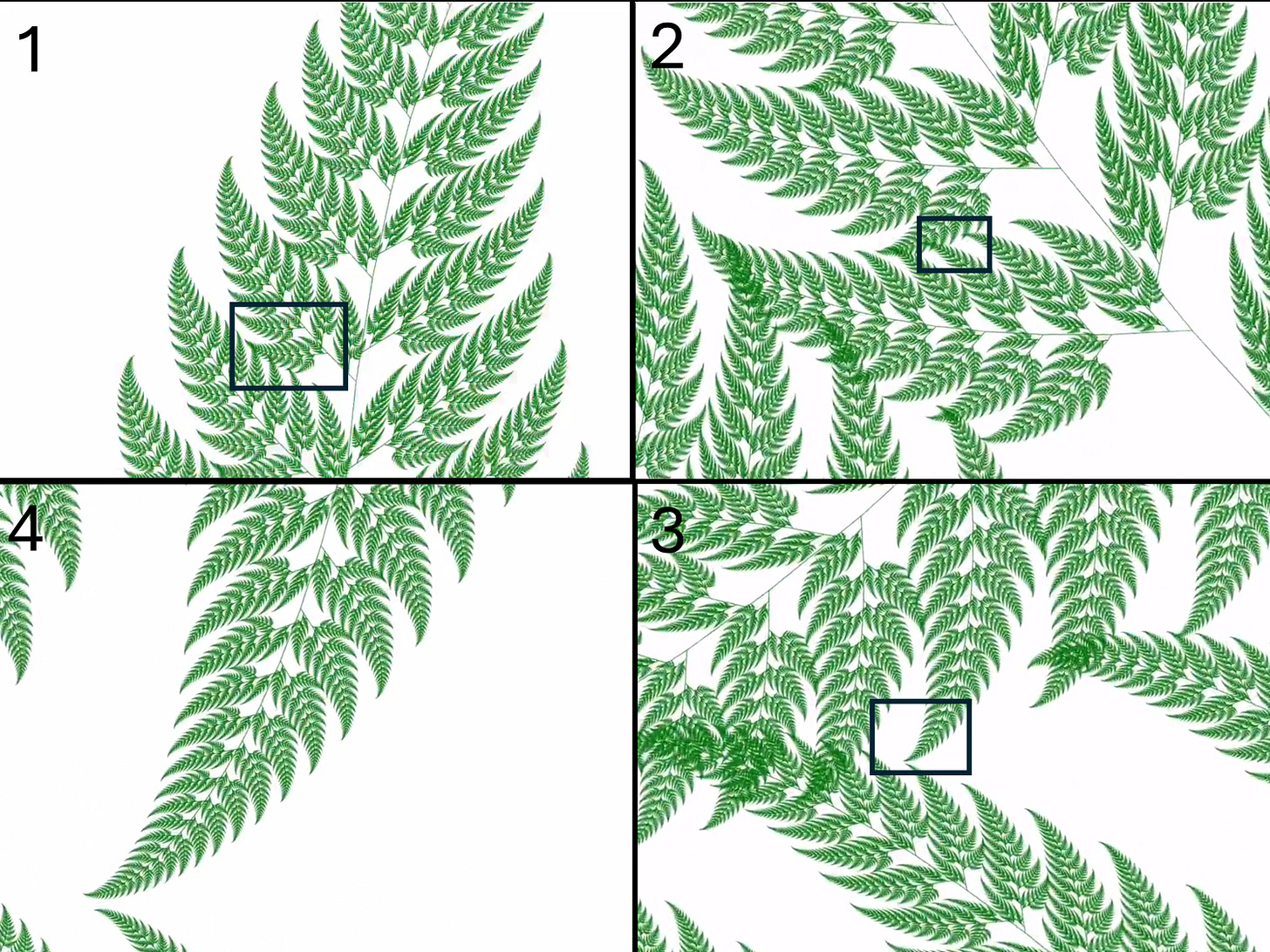

Iteration is also how the past and present threads of Arcadia speak to each other. Thomasina writes an equation she can only push so far with pencil and paper; two centuries later Valentine runs it millions of times and recognises a shape hiding inside the numbers, “patterns making themselves out of nothing,” each image “a detail of the previous one.” The play dubs the result the “Coverly set” – a fictional mathematical object that anticipates the twentieth-century discovery and popularisation of fractals.

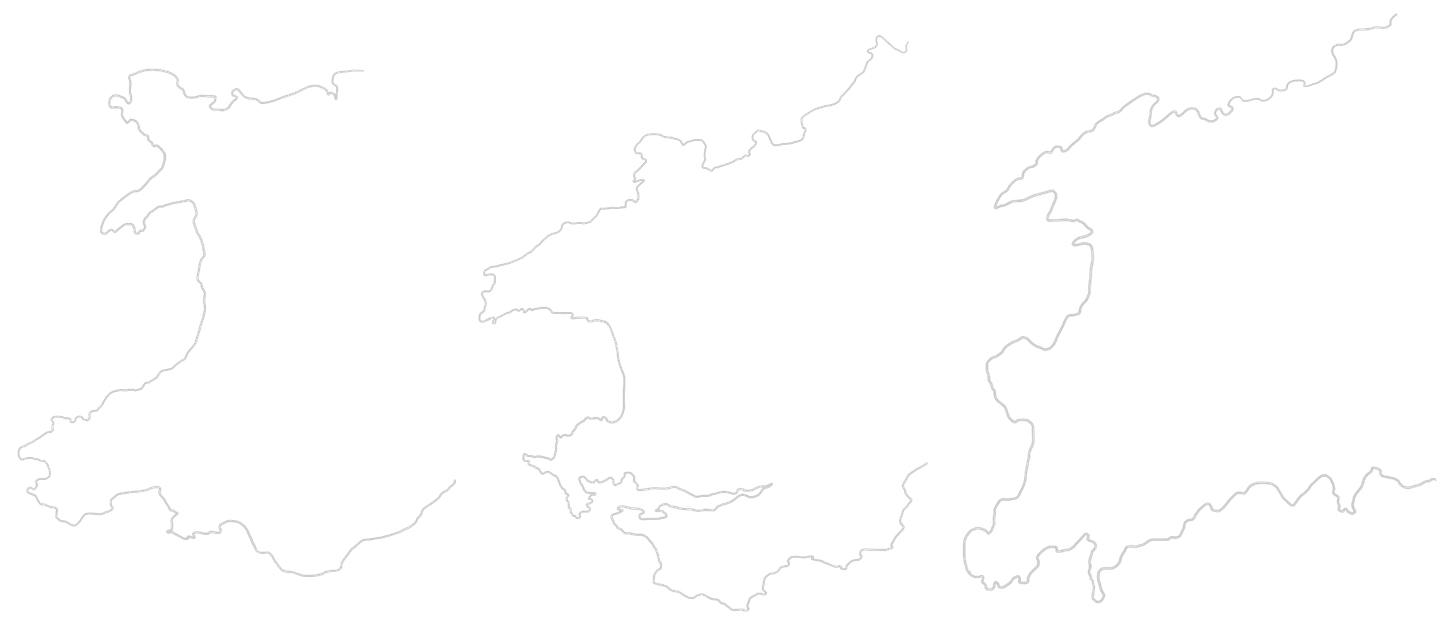

Fractals - A geometry for leaves, clouds and coastlines

Thomasina bristles at a classroom geometry that reduces nature to cones and pyramids. “Mountains are not pyramids and trees are not cones,” she observes, and she sets out to find “an equation for a leaf.” Long after her fictional lifetime, mathematicians would coin “fractal geometry” for shapes that are rough, detailed and self‑similar: zoom in and the local structure echoes the global one. The fern, a classic example, behaves exactly this way; so do coastlines and the swirling borders of clouds. The mathematical moral is startling and theatrical at once: simple iterative rules can generate images of astonishing complexity.

Stoppard makes the connection explicit by invoking ideas associated with fractals and their chief mathematical proponent Benoit B. Mandelbrot. Thomasina’s quote about mountains and trees is only a very slight paraphrase of Mandelbrot’s famous quote “Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line”. In Arcadia that idea of self-similarity becomes an aesthetic too: scenes replay motifs at new scales, gestures recur in altered guises, and the audience slowly learns the larger pattern by encountering its smaller echoes.

Time only runs one way: heat, entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics

Not every law is as forgiving of a reversal as Newton’s laws. As Thomasina realises in 1809, when you stir jam into rice pudding you might reverse the direction of your spoon and go back the other way, but the jam will never stir itself out. As Valentine points out in 1993, if you leave a cup of tea it will cool by itself; no cup sits on the table and grows hot by borrowing warmth from a colder room. These domestic truths are the fingerprints of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: in an isolated system, total entropy - a measure of spread or disorder - never decreases. Arcadia gives the idea memorable dialogue. “You cannot stir things apart,” Thomasina protests, and Valentine supplies the overarching summary: “Heat goes to cold. It’s a one‑way street… we’re all going to end up at room temperature.” – hinting at the eventual heat death of the universe.

The play also brings the audience towards a technical crux. Newton’s equations are time‑symmetric; the heat equation is not. Popular explanations capture the vital physics and the ultimate consequence of the Second Law of Thermodynamics as the arrow of time: the reason the film of a pool break looks wrong when run backwards is that the balls seem to spontaneously become more ordered rather than spreading out – as they do when the film is played forwards. Arcadia lets that irreversibility resonate beyond physics, in the way reputations spread, lives unfold, and knowledge is lost or found.

A margin note that launched a centuries‑long chase

Another thread follows a different kind of persistence. Pierre de Fermat once wrote in the margin of a book that he had a “truly marvellous proof” that the equation

xn+yn=zn

has no for whole numbers, x, y and z and for whole number n greater than 2, but that the margin he was writing in was too small to contain it.

The note outlived him and taunted successive generations of mathematicians until Andrew Wiles, in 1993 (coincidentally a few months after Arcadia premiered), finally announced a proof. Within the play, Fermat’s Last Theorem becomes a symbol of patience, obsession and the way ideas are handed forward even when individuals are lost to time. We learn in the 1993 timeline that Thomasina has even written, in the margin of her notebook: “This margin being too mean for my purpose, the reader must look elsewhere for the New Geometry of Irregular Forms discovered by Thomasina Coverly.” A prescient echo of the discovery she makes in the play.

A science play - but never a lecture

Arcadia is ultimately about learning - its pleasures, its errors and its costs. The scientific content is never there as a lecture; it’s there to provide depth to the characters. Thomasina’s restlessness with her iterated algorithms speaks to her curiosity as a prodigious teenager; Valentine’s insistence that he’s studying the “behaviour of numbers” rather than grouse speaks to a researcher’s stubbornness; Septimus’s rueful grace about what must be lost recognises the limits of anyone’s lifetime. The mathematics amplifies a human theme: we do not inherit certainty; we inherit questions and methods, fragments and false leads, a table strewn with notes and drawings that we try to make sense of before we, too, have to put the pen down. Or, as Septimus puts it, “We shed as we pick up, like travellers who must carry everything in their arms, and what we let fall will be picked up by those behind… The procession is very long and life is very short. We die on the march. But there is nothing outside the march so nothing can be lost to it.”

None of this requires you to solve an equation on your way into the theatre, but it might help you to keep these three simple ideas in mind if you do go and see the play. First, a perfectly predictable rule can still yield outcomes that resist long‑range prediction. Second, complexity can come cheaply, nature encodes much of its beauty in repetition and feedback. Third, some processes can never be undone, and that irreversibility gives time its felt direction. The brilliance of Arcadia is to let those ideas surface through wit, flirtation, rivalry and grief, so that when someone stirs jam into pudding or watches steam drift from a cup of tea, you don’t hear a lecture but the existential musings of another human being.

Splendid, a beautiful note for the play. I would love to make the trip south, but guess I am too deaf.

Co-incidentally a few days ago I was pointed to Roger Tempest who alternating at times with Richard, re-iterated across centuries. There is a Wikipedia page, but this catches the flavour of history and its uncertainties. These were recusants, so the Ladychapel survived. https://fmg.ac/phocadownload/userupload/foundations3/JN-03-01/037Tempest.pdf

PS 'The Country House' in England can be more than a cliche plot. Fred Hoyle, Astronomer Royal, located 'The Black Cloud', a good Sci Fi yarn, in an echo of 'Bletchley Park', with another brilliant mind, and a fated search .

The best article I've read in quite a while. Brilliant. Thankyou