COVID Inquiry: Lessons on the importance of independent scientific advice

We must ensure the independence of scientific advisers from the politicians they advise.

The reporting of some of the evidence from the UK’s Covid Inquiry this week has felt a little bit like a circus. Chief political correspondents have been drafted in to covering the drama, as civil servants and special advisers (SPADs) at the heart of the Johnson government have been summoned to give evidence. Understandably, the reporting has tended to focus on the sensational: the misogyny, the insults, the infighting between different factions and the general incompetence of those in charge.

But it’s easily forgotten that one of the main focusses of the Inquiry is to learn lessons for the future to prevent the calamitous mistakes that were made during the acute phase of the pandemic from happening again. In amongst the diet of snipes and sensationalism are buried important nuggets of information from which we can derive lessons for our future scientific response.

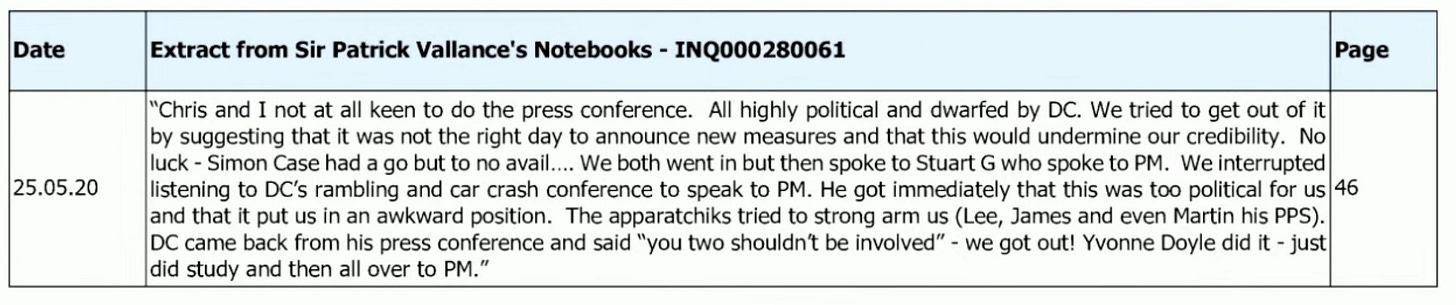

For me, one of the most damning revelations went almost unreported this week. Buried in an excerpt from Patrick Vallance’s diaries (see below) he describes himself and Chris Whitty being “strong-armed” by senior civil servants into appearing at a press conference at which the Prime Minister would be defending Dominic Cummings’ trip to Barnard Castle.

Figure 1: An excerpt from Patrick Vallance's diary in which he describes himself and Chris Whitty being “strong-armed” into appearing alongside government ministers.

This illustrates a very real problem for the scientific advisory system in our country. How can the independence of scientific advisors be maintained under these circumstances? Scientist must be independent of the politicians they are advising. More than that, they must be seen to be independent and that means being able to speak freely about important issues relevant to the crisis.

Professor Yvonne Doyle’s Inquiry testimony presents a stark example of the sort of censorship experience by scientists during the acute phase of the pandemic. In January of 2020, the then medical director for Public Health England undertook an interview on BBC Radio 4’s today programme. In the piece she candidly admitted there could well already be covid cases in the UK and that it would take months if not years to develop a vaccine (see transcript below from CNN).

Figure 2: A transcript of Professor Yvonne Doyle's interview on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme for which she was later reprimanded (source: CNN).

Following the interview she was advised “not to do any further media, and that the secretary of state [for Health and Social Care - Matt Hancock] would need to clear all media”, which, given little choice, she agreed to. Professor Doyle found herself effectively frozen out, told to stay away from Hancock, so annoyed was he with her intervention. One of the UK’s most senior scientific officers was unable to give effective direct input into the UK’s response at an extremely vital stage of the pandemic, and all because she spoke freely and truthfully to inform the public of the emerging covid situation. It’s almost unbelievable.

One of the most senior civil servants at the Department for Health and Social Care, Sir Christopher Wormald, expressed his concerns that Downing Street SPADs were attending SAGE meetings in April 2020. He feared that the political presence was compromising the “purity” of the scientific advice being given to the government at the time. Giving an example of the sort of changes induced by the attendance of SPADs he recalled “As far as I could see, SAGE had changed its analysis, particularly around, I think it was, the effects on the NHS without there being an explanation of new data.”

This concern over the potential political interference with SAGE was one of the reasons (alongside the lack of transparency in SAGE membership and advice) why Independent SAGE was set up by Sir David King (former government Chief Scientific Adviser) in May of 2020. The idea was to create a group of scientific experts who could give advice to the government - and crucially directly to the public - without the worry of political interference. This is what we have done and continue to do through regular live-streamed public briefings, on to which members of the public are invited to ask questions directly of Independent SAGE members, and through regular publicly accessible reports and situation updates.

For me, the public communication aspect of Independent SAGE has always held the utmost importance. If the general public are being asked to undergo restrictions on their lives and livelihoods based on scientific advice then I believe it is incumbent on scientists to explain to the public the rationale behind those decisions. It’s also of vital importance that scientists feel able to speak out when they become aware that political leaders are taking decisions or actions which are unsupported by scientific evidence.

What is so disappointing to see in the entries from Sir Patrick Vallance’s diaries that have thus far been presented as evidence at the Inquiry is that his privately held views are so different from his publicly stated position. In his diaries he describes the Dominic Cumming’s trip as “Clearly against the rules” but never said so publicly. In other entries he describes Boris Johnson’s indecisiveness, inconsistency and constant “flip-flopping” – attributes we all suspected but would have shed light on the chaos at the heart of the government’s covid response and allowed us to demand better.

In June 2020 Vallance privately accuses ministers of “cherry picking” the advice they liked from SAGE, but never once publicly contradicts the government’s claims to be “following the science”. In another entry he suggests his meetings with ministers have made it abundantly clear that “no one in No 10 or the Cabinet Office really read or is taking time to understand the science advice…”.

These are crucial views which, if expressed publicly, would have given us insights into exactly how the people in power - whom we expected to protect us - were in fact cooking up rules and policies unsupported by scientific evidence.

One needs only look at the catastrophic impact of Eat Out to Help Out, a scheme which it later emerged SAGE was not consulted about. One SAGE member - John Edmunds - expressed his criticisms of the scheme in the strongest terms: “If we had (been consulted), I would have been clear what I thought about it. As far as I am concerned, it was a spectacularly stupid idea and an obscene way to spend public money.” But these critiques were aired in the summer of 2023, long after it was useful for the general public to hear them.

One of the main aims of the Inquiry is to learn lessons about our response to future such crises. One lesson which surely cannot be ignored, given the evidence we have heard this week, is the vital importance of the separation of scientific advisors from the politicians they advise. This means no political appointments influencing scientific meetings. It means rendering politicians unable to censor scientists in their attempts to communicate science with the public. And it means scientific advisors being able to speak freely, publicly and contemporaneously about the scientific advice they are giving and, in particular, when that advice is being ignored or contradicted by government policy. Without these guarantees on the independence of our scientific advisors we will undoubtedly face the same problems again the next time a crisis hits.

Came here via your twitter thread on Boris Johnson's innumeracy. Before I get started, note that I am no fan of the tories, or Johnson.

Johnson's failure to grasp the statistics presented to him falls into the category of human error, not stupidity. The inability to correctly interpret statistics when presented as percentages is something that affects the population as a whole, including medical professionals. Most infamously, the false positive rate in HIV testing was presented to patients and professionals alike in terms of percentages, which had the knock-on effect of men taking their own lives as a result of their misunderstanding. Gigerenzer has published extensively on methods of presenting statistical information which dramatically reduces such misunderstandings, yet these simple methods have not percolated to people who discuss statistics with people who are not immersed in statistics for a living. In this case, the fault lies with those who presented the figures.